Endangered and threatened species could one day be translocated to a fenced area on the Nullaki thanks to the efforts of local landholders and the Wilson Inlet Catchment Committee (WICC).

A finger of land bordered by the Southern Ocean to the south and Wilson Inlet to the north, the Nullaki is separated from the mainland by a seasonal sandbar to the west at Ocean Beach and a feral-deterring fence on its eastern edge. Installed in the 1990s, the fence has fallen into disrepair in recent years, but is being repaired and improved by WICC.

Volunteers like Nullaki resident David Barr have been monitoring the peninsula for native fauna, installing cameras, cat and fox traps and 1080 baits, and releasing Calicivirus to control rabbit numbers, preparing the ground for what they hope could become a future sanctuary for threatened species.

Nullaki means place of seaweed in Noongar, and originally described the waters of Wilson Inlet and its surrounding landforms by the Menang and Pibbulmun people who lived there. Used for grazing by early European settlers, the Nullaki later became a popular playground for the nearby town of Denmark, with 4WD tracks crisscrossing the sand dunes between the inlet foreshore and the limestone cliffs that fall into the Southern Ocean.

The peninsula was purchased by property developer Graeme Robertson in the 1990s and developed into a conservation estate protected by a vermin-proof fence, with an electronic gate allowing access to residents and visitors.

Shaun Ossinger, WICC’s executive officer, says while the original fence was never completely vermin-proof, changes to its structure and design will help keep foxes and cats out of the fenced area. Almost half of the 8km long fence has been replaced, with a new floppy top being added along its entire length to stop feral animals climbing over. Another 500m of fence posts have been replaced, with a completely new section of fence installed in 2019.

“If you could see it two years ago: it was lying down in sections and there were holes in it,” Shaun says. “The kangaroos would come and box each other through the fence.”

While COVID19 stalled the new fence’s installation, the project is back on track to be finished by this winter. And Shaun says the involvement of landholders has been critical to the project’s success.

“Having a relationship with the landholders is essential. It is all private property so everything we do, we have to get permission from a bunch of people and, depending on what the intention is, they may be more or less amenable to it. Some of them are virtual relationships where we know each other through emails, but they live overseas.

“Without people like David, this would never happen.”

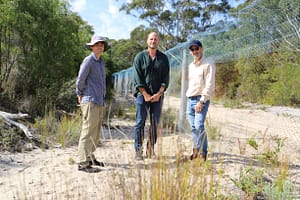

David and Nullaki Conservation Initiative volunteers Craig Carter and Fred Morino have been working on feral animal control measures that complement the fence repairs. Four cats were trapped inside the fenced area over the Easter holiday period: the cats taken to Youngs Siding vet Shey Rogers, who evaluated and checked the cats for a microchip before humanely euthanasing them.

“These are feral animals, not moggies,” Shaun says.

“There is a diversity of remnant vegetation types here. There is almost habitat for everything, from noisy scrub birds to the Western ringtail possum.”

David and his wife, WICC chair Joann Gren, have owned their Nullaki property for 15 years, moving south to live on the bush block seven years.

The couple have helped with community fauna surveys and installed camera traps on properties along the fenceline and sandbar. David says they have found mardos (also known as yellow-footed antechinus: a small, mouse-like marsupial) and honey possums, black cockatoos and evidence of brush-tailed phascogales.

“I think for the most part, most people are conservation minded when they buy out here,” David says. “We are not really land–owners, we are custodians of our block.”

The Nullaki Conservation Initiative is made possible through coordination by WICC and the support of many stakeholders, including South Coast Natural Resource Management, and funding from the Western Australian Government’s State Natural Resource Management Program and the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program.